Carriages

A prizewinning LMS Open by Stephen

Williams.

With wagons we were dealing almost exclusively with four-wheeled vehicles, now it is the turn of bogie vehicles. Again, because we are using scale flanges on our wheels, we must ensure they are always in contact with the rail, and once more the choice is between compensation and springing; the good news is that for conversion to P4, you just work on the bogies. In most cases, it is preferable to build new bogies. Should the reader be interested principally in passenger trains, he may prefer to build, say, two pairs of bogies instead of two wagons, perhaps one sprung and one compensated, rather than the wagons suggested in the previous section.

As with wagons, let us begin

with compensation, although with carriages the move from compensation

to springing is more pronounced than it is with wagons. With coach

bogies, rather than have one pair of wheels in each bogie rocking

usually it is the bogie sides which twist slightly to give the same

result, namely keeping all four wheels in contact with the rail. The

Scalefour Society sell their own kits using beam-type suspension,

while the MJT torsion type are now retailed by Dart Castings, and

Comet offer a compensated bogie.

As with wagons, let us begin

with compensation, although with carriages the move from compensation

to springing is more pronounced than it is with wagons. With coach

bogies, rather than have one pair of wheels in each bogie rocking

usually it is the bogie sides which twist slightly to give the same

result, namely keeping all four wheels in contact with the rail. The

Scalefour Society sell their own kits using beam-type suspension,

while the MJT torsion type are now retailed by Dart Castings, and

Comet offer a compensated bogie.

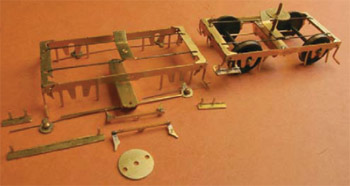

If anything, springing is somewhat easier with carriages than with wagons and Bill Bedford, Michael Clark and David Bradwell all have systems on sale. David is the agent for the Mitchell-Pendlenton type which gives not only primary suspension but a degree of secondary suspension also. All of the above designs consist of a basic bogie frame and require the addition of cosmetic sideframes. They all use pin-point axles running in the same standard cup-type bearings as are used for wagons.

Because we use grossly tight curves, compared with the prototype, on almost all models our bogies inevitably turn far more than they should and P4 wheels, being wider overall than OO ones, may scuff on the inside faces of the solebars. This is especially true of carriages with plastic underframes and gentle work in this area with the router may be required to remove a little material from the inside faces.

It is also a good idea to allow a little horizontal rock (so that the back and front can rise and fall slightly) on the bogies. With wagons we considered the case of a slight dip in one rail and this will be coped with by bogies too, but what is more pernicious - and less easily discovered - is a dip over a longer distance, say 300mm, called 'twist', which is why a little horizontal rock for one bogie is beneficial. And for our final caveat, it should be pointed out that the 25gram per axle weight recommendation, that is 100 grams for an eight-wheeled coach, still applies.

And, yes, before someone points it out, not all coaches are bogie vehicles; there are six-wheelers too. Many and wonderful were the solutions devised by Victorian engineers to the full-size sixwheeler problem and by all accounts none resulted in a terribly smooth ride. The best seems to have been the eponymous system of Mr Cleminson. We are fortunate that a model variant has been developed by Brassmasters especially for P4. In our experience it works well, but I'm still no great fan of the type in general.

So

far we have looked at locomotive-hauled carriages, ignoring

self-propelled vehicles, electric and diesel. Here the bogies have not

only to give a good, smooth ride, they have to pick up current and

provide power too - and stay on the track while so doing.

So

far we have looked at locomotive-hauled carriages, ignoring

self-propelled vehicles, electric and diesel. Here the bogies have not

only to give a good, smooth ride, they have to pick up current and

provide power too - and stay on the track while so doing.

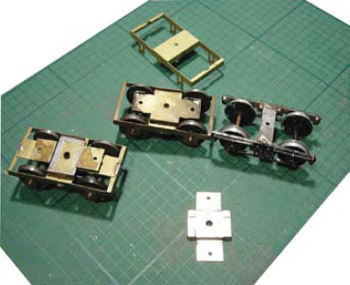

Most modellers nowadays seem to be modifying ready-to-run bogies, and this seems to apply to diesel and electric locomotives too. Certainly, drop-in wheelsets are available to help with this, and the running which results is almost invariably good. And they look good on the move too, on the properly scale track of P4.